An Essay by The Fall Color Guy – Howard S. Neufeld

Were you to have gone to the mountains to view fall leaf colors in 1904, your experience would have differed greatly from what you see today. For starters, there wouldn't have been as many roads (the Blue Ridge Parkway was still 3 decades away from being built), most of the high country roads would have been dirt (50% of the roads in Watauga County, NC, where I live now, and home to Boone and Appalachian State University, were unpaved as recently as 1987!), many hillsides would have been in pasture, without any trees, as that period of time was when timbering reached its peak in this area, and finally, where trees were still standing, one quarter of them would have been just one species, the American chestnut (Castanea dentata).

Photo of large American chestnut in central Maryland around the turn of the century. Library of Congress.

Today, there is no shortage of roads, and the Blue Ridge Parkway runs for 469 miles from just south of Shenandoah National park in Virginia to the entry of Great Smoky Mountains National Park in NC, providing unequaled vistas for viewing fall leaf colors. In fact, on peak weekends, the Parkway can get backed up so bad that it's often better to get off and explore the nearby country lanes where you can experience the fall colors in relative isolation.

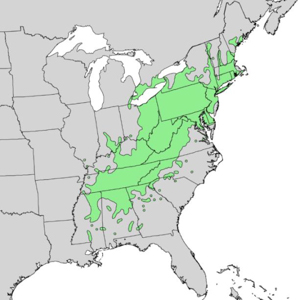

Original range of American chesnuts. USDA.

It also helps that many of the roads in the High Country are now paved, which saves on tire wear, increases safety, and decreases erosion and silting of adjacent forest lands. Even more important, many of the turn-of-the-century pastures were let go and have reverted back to forests, and we actually have more forests in some areas now than we did a century ago. That of course, provides additional areas to view fall leaf colors.

But the one aspect of fall color that has yet to improve is the status of the American chestnut.

As you probably know, a fungal parasite decimated most of the estimated 3 billion chestnut trees on the east coast. Although accidentally introduced as a hitchhiker on imported chestnut trees in 1876, it was first noted killing American chestnuts in 1904, and just a few decades later, had wiped out the majority of this once majestic species. However, the species will sprout from the root systems, and while still widespread, it grows more like bush now than tree. When it gets several inches in diameter, the fungus (see below) attacks the stems and knocks the tree back down to just sprouts.

Map showing rapid progression of the chestnut blight, caused by the fungus Cryphonectria parasitica (formerly Endothia parasitica) down the east coast. Courtesy of the Joplin Globe newspaper.

Granted, this species didn't have great fall color – chestnuts turn yellow, then brown, before falling off. But its abundance would have resulted in a more prominent yellow background against other trees that turn either orange or red, such as maples, oaks and sourwoods. Today, that yellow color is provided by tulip poplars (also known as yellow poplar), birches, beeches, and magnolias. It's a shame we don't have good fall color pictures from this period (maybe some exist, but I've never seen them – if you know of any, let me know).

Loggers around 1900-1901 in the southern Appalachians in a grove of very large American chestnuts. Library of Congress.

So, is the American chestnut gone for good? Don't bet on it. There are several organizations working to bring this iconic tree back to our eastern forests. The American Chestnut Foundation, based in Asheville, NC, has been breeding blight-resistant Chinese chestnuts into the susceptible American chestnuts, and by backcrossing them, has created a blight-resistant tree that is 15/16ths American chestnut, yet has the growth form of the American chestnut. Farther north, at the Forestry School at Syracuse University, researchers are working to introduce new genes into the chestnuts that confer resistance to the blight. If they get approval, their trees could be the first genetically modified trees allowed into the natural landscape (see, not all GMOs are bad – in fact, as best we can determine NO GMOs have any adverse effects on people – most people simply have an irrational fear of them).

Chestnut sprouts showing their yellow fall leaf color. Jefferson State Natural Area, NC. Photo by author.

I won't attempt to go over the history of chestnut blight or its aftermath, as that has been done numerous times before. Instead, I provide a list of excellent websites with articles on this (see below). I will mention, though, that one of the secondary effects of the loss of the chestnuts was the change in species composition of our forests after these trees died out. It's thought that the ecological niche formerly occupied by the chestnuts was taken over by oaks and hickories, as well as red maples, which of course, probably greatly altered the color composition of these forests during the fall. In some areas, especially on moist, north-facing slopes, the opening of the canopy may have contributed to the increased abundance of Rhododendron maximum, a native, evergreen shrub that now covers thousands of acres of forest understory in the southeastern mountains.

Canker on chestnut stem resulting from blight infection. The blight produces oxalic acid, and disrupts water and nutrient flow to the trees, killing them. Wikipedia.

These changes to the forest also present serious problems for re-establishing American chestnut in our eastern forests. How do you, so to speak, "squeeze" a new species into an old "niche" in a forest whose niches are now occupied by other species? Can you simply plant seedlings and allow them to grow and out-compete the existing species, or do you need to "help" them along until they get big enough? Should you plant them out in the open, or in the forest understory? Will deer eat them before they can grow large enough to avoid herbivory?

All of these questions are being addressed by researchers now. In fact, a new collaborative project between the Army Corps of Engineers and the American Chestnut Foundation, with future research assistance from ecologists at Appalachian State University, will be starting soon in a forest near Kerr Scott Reservoir outside Wilkesboro, NC. Some 1,000 chestnut seedlings of various sensitivities to the blight will be planted in both open fields and beneath existing forests in an attempt to answer these very questions. Only time will tell which treatment leads to the most successful establishment of this species.

Finally, another wave of extirpation (loss) of a tree species is occurring throughout our forests now, and that is the unfortunate decimation of our beloved eastern and Carolinia hemlocks as a result of attack by the exotic and deadly hemlock adelgid. This nasty foliar pest has killed millions of hemlock trees up and down the east coast, and there is no easy solution to this problem yet. There does not seem to be the same option of breeding resistance into our native hemlocks to fight off this insect pest as was possible for the chestnut. There have been some attempts at biological control, but they have not been very successful yet. But who knows, maybe something can be done in the future. In the meantime, a stark landscape of dead, gray trees splayed against a green background of more healthy trees will become a common site for the foreseeable future.

Hemlocks in Michigan killed by the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (Adelges tsugae), a close relative of the adelgid that has wiped out 95% of the Fraser firs in the southern Appalachians. Photo from Grand Haven Tribune, Aug 14,2015.

Here are those websites if you want to read more about American chestnuts:

The Atlantic – May 13, 2013 – a nontechnical article on the attempts to bring the chestnut back:

http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/05/genetically-engineering-an-icon-can-biotech-bring-the-chestnut-back-to-americas-forests/276356/

A somewhat dated (2004) article about Professor Doug Jacobs, from Purdue University, who is working to re-establish chestnuts in Indiana:

http://www.purdue.edu/uns/html4ever/2004/040329.Jacobs.chestnuts.html

A short article about chestnuts from the Mountain Lake Biological Station:

http://www.mlbs.virginia.edu/organism/americanchestnut

This article describes in great detail the situation regarding chestnuts and the attempts to bring them back. Perhaps the best article every written on this:

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/chestnut-forest-a-new-generation-of-american-chestnut-trees-may-redefine-americas-forests/

A Washington Post article on reviving the American chestnut:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/food/unearthed-thanks-to-science-we-may-see-the-rebirth-of-the-american-chestnut/2014/11/19/91554356-6b83-11e4-a31c-77759fc1eacc_story.html

Here is the official website of the American Chestnut Foundation:

http://www.acf.org/

Here is the official website for the researchers trying to introduce genes to confer blight resistance in American chestnuts:

http://www.esf.edu/chestnut/

This is a short article about bringing back the American chestnut from the magazine American Forests:

https://www.americanforests.org/magazine/article/revival-of-the-american-chestnut/

Here's how Nature, one of the foremost science magazines, reports the chestnut issue:

http://www.nature.com/news/plant-science-the-chestnut-resurrection-1.11504